Dark Fibre Network Drift (2019)

By

John Wild

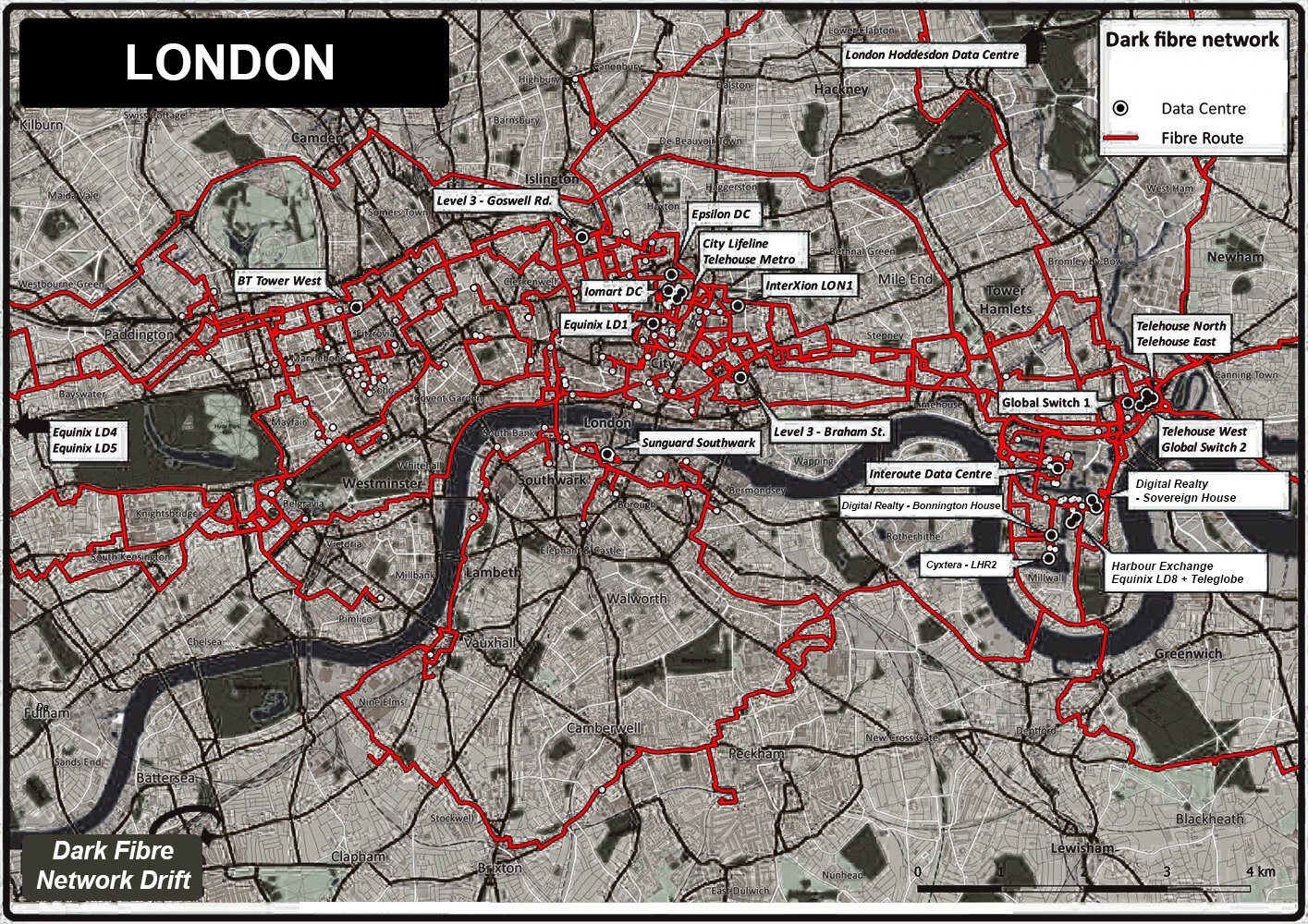

Map of London's Dark Fibre Network. Image credit: John Wild.

We followed the rout of underground fibre-optic cables linking the core data centres that form the London Internet Exchange.

Dark Fibre Network Drift was a collective walk, organised by John Wild, following the route of underground fibre-optic cables linking the core data centres that form the London Internet Exchange. The walk included spoken word by Robin Bale and experiments using software defined radio to hack the sonic world of machine to machine communications. Around 30 walkers met at 14:00 on Sunday 27 October 2019, Chrisp Street Market, Poplar, East London.

When telecommunications companies lay fibre-optic cable, they lay extra to mitigate the future cost of having to lay it again. Dark fibre refers to the unused fibre-optic cables. The walk used a map of London’s underground dark fibre network to chart a route through East London that focused on the central nodes in the UK’s internet. Our first destination was Coriander Avenue, a 15-minute walk from Chrisp Street Market, on the south side of East India Dock Road. Coriander Avenue is a nexus point in the London Internet Exchange (LINX) and, by definition, within the UK's internet infrastructure.

Coriander Avenue and its surrounding streets, Saffron Avenue, Nutmeg Lane, Rosemary Drive and Oregano Drive, house four of the core LINX data centres: Telehouse North, Telehouse North 2, Telehouse East and Telehouse West. Alongside the four Telehouse data centres is the Global Switch Campus, comprising two data centres, Global Switch London East and London North. Global Switch London East hosts financial services customers and enterprises including Google, Fujitsu, Claranet and Datapipe. Global Switch North is the termination point of Atlantic Crossing 1 (AC1), the main subsea optical submarine telecommunications cable system, linking the UK directly to the United States.

From Coriander Avenue, the walk followed an arm of the dark fibre network south past Sovereign House and Meridian Gate data centres, to Equinix LD8 which houses Amazon’s UK servers. The experience of walking these sites was powerful. The buildings are imposing, anonymous and secretive and induce a self-consciousness in those who enter their terrain. The physicality of the data centres exposed their integration into wider networks of infrastructure, in particular their use of electricity.

Telehouse North Two, for example, contains its own on-campus 132 kV grid substation that is directly connected to the National Grid. Such heavy demands for electricity raise important questions about both the environmental impact of cloud computing and why so much data is being stored. The confrontation with the sheer scale and physicality of cloud computing is one of the fundamental strengths of investigating the digital city through walking.

We are sold a belief in cloud computing as light, impermanent and invisible. The reality is imposing, industrial and infused with a paranoia-inducing hostile ambience. The walk enabled a collective confrontation with the materiality of the UK’s internet infrastructure that challenged the ephemeral image of cloud computing and created an event where new spatial imaginaries could emerge through the practice of walking and talking together.

To read the Dark Fibre Network Drift publication, scroll through the document below:

“One of the things that I really enjoyed about the walk was meeting interesting people that I had no reason to meet prior to. As we walked I found myself moving between different groups, having conversations and noticing different things. John pointed out the manhole covers and the way to spot and follow the traces of the underground fibre-optic cables. I became hyper-aware of their existence on the footpaths, where I had not noticed anything before. It gave me an understanding of the significance and number of different companies, crisscrossing the paths. I still notice the manhole covers and imagine peoples’ data flowing through the city below my feet. As we walked we crossed roads that passed through different territories. I noticed islands of bizarre new housing developments that were for sale as investment properties that would never be occupied. This seems criminal when there’s a housing crisis. Robin Bale’s poem by the side of the road, with the constantly moving traffic, noise, pollution, overall immensity of the buildings and imposing nature of the architecture was really thought-provoking and enabled me to look at the area of East London, which I thought I knew well, in a totally different light. I was shocked by the scale and size of the data centre buildings, how grey and inaccessible they were, even though they were next to housing developments that felt quite alive. Detecting the electromagnetic sounds of the data centres using a handheld device, was quite ominous and I was constantly aware that someone was going to try and stop us. In fact, we were confronted by security and told not to take pictures of what appeared to be buildings on a public street! I remember a particular moment when the radio sniffer device picked up and amplify a mobile phone conversation, very freaky. For me, the best thing was meeting different people and the conversations that I had along the way. Conversations that made me think about everything from the gentrification of the East End, the way tech companies use our data and the impact of cloud computing on climate change.”